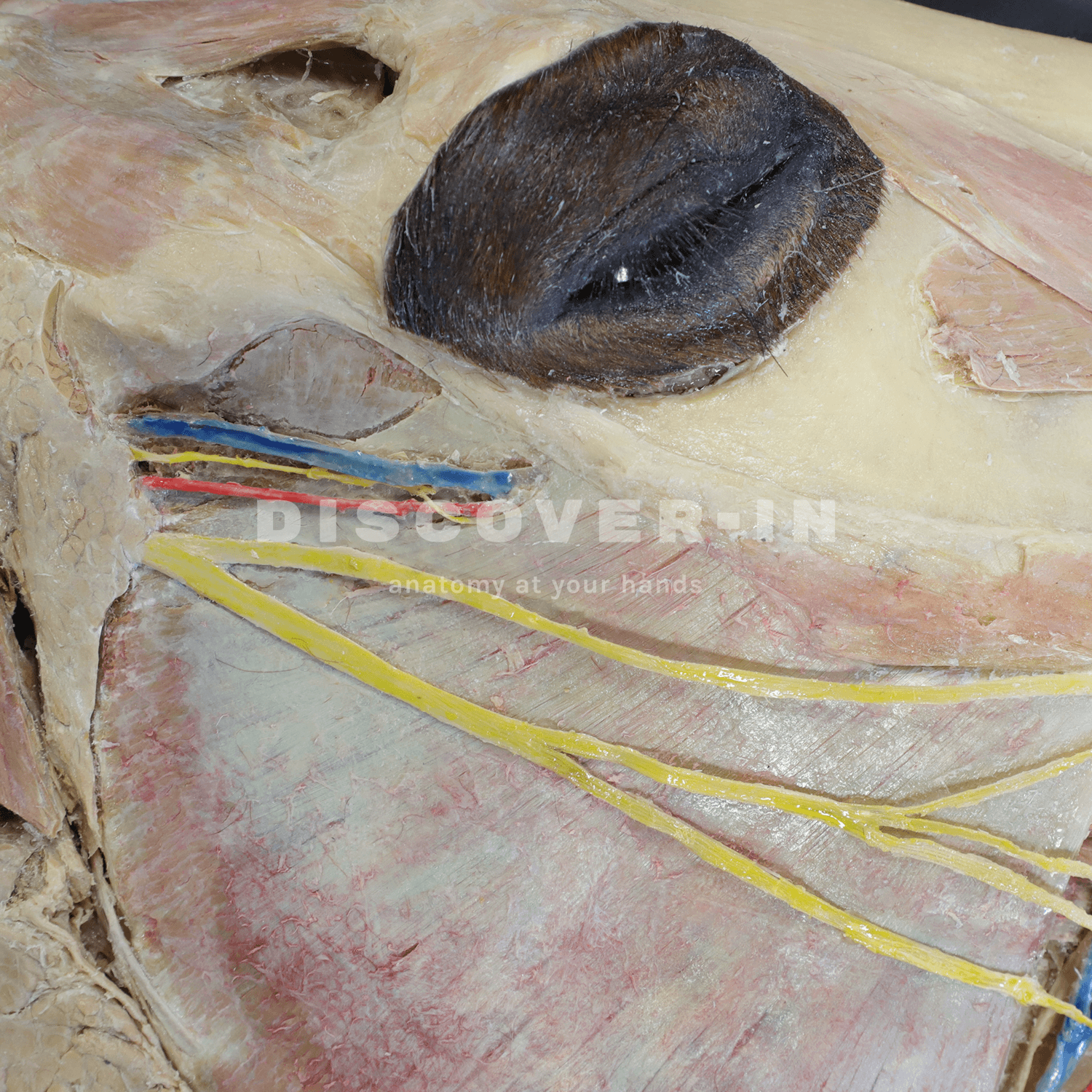

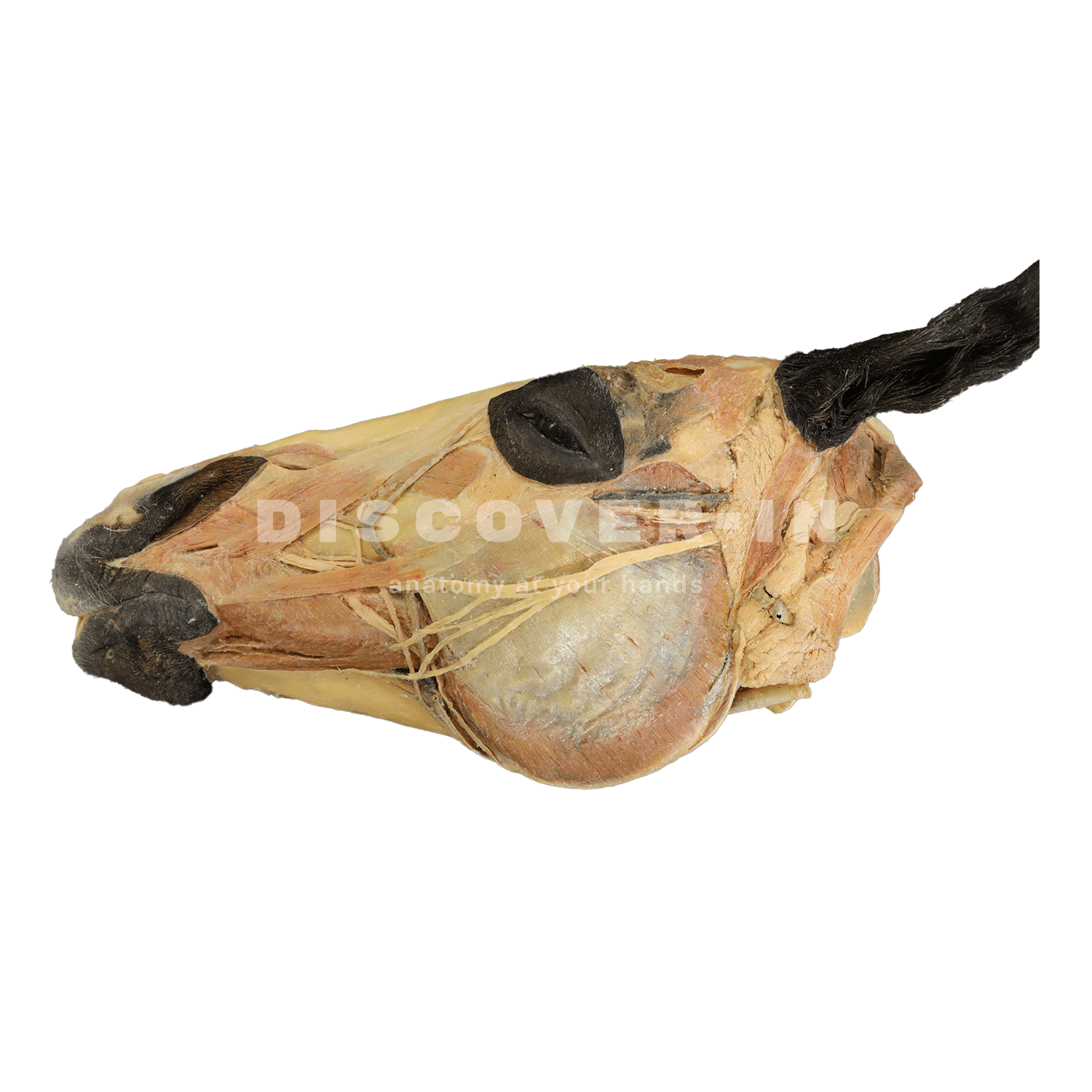

This equine hemisection shows a superficial dissection of the lateral aspect and a sagittal middle section.

If you have access to our plastinated specimens, you will be able to deepen your anatomical knowledge in a practical and hands-on way.These specimens will enable you to:

• Precisely identify key anatomical structures.

• Understand anatomical reality in detail.

• Reinforce theoretical learning.

• Strengthen the acquisition of practical and clinical skills.

These advantages make Discover-IN specimens an innovative resource for students, educators, and professionals seeking comprehensive, effective, long-lasting, and biologically safe training in veterinary anatomy.

This plastinated horse head specimen clearly reveals the main bony structures, facial musculature, and detailed features of the nasal, oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal cavities, as well as relevant vascular and nervous structures such as the facial artery, linguofacial vein, and buccal branches.

Furthermore, this specimen is also available in a digital 3D and augmented reality version at:https://discoveranatomy-in.com/app/landing

The horse’s head is one of the most complex and functional regions of the equine body. It brings together bones, muscles, nerves, and blood vessels in perfect coordination, enabling essential functions such as chewing, breathing, sensory perception, and facial expression. Understanding this anatomy with precision is not only critical for clinical diagnosis and veterinary practice but also for modern anatomical education.

Main Parts of the Horse’s Head

1. General Structure of the Equine Skull

The equine skull is a highly intricate structure composed of flat, irregular, and pneumatic bones that protect the brain and sensory organs. Beyond protection, it serves as the anatomical foundation for chewing, smell, vision, and hearing.

Its architecture can be divided into three main regions:

- Cranial region: houses and protects the brain.

- Facial region: contains the sensory organs and the respiratory and digestive cavities.

- Mandibular region: responsible for jaw movement and the mechanics of chewing.

Together, these regions maintain a delicate balance between protection, mobility, and sensory function, essential for the horse’s behavior, athletic performance, and overall health.

2. Bone Structure: The Pillars of the Equine Skull

The most relevant bones include the frontal, parietal, nasal, maxillary, zygomatic, and mandibular bones.

The maxilla and mandible support the dentition and play an active role in grinding and processing food, while the zygomatic arch shapes the facial contour and serves as a key attachment for chewing muscles.

The occipital bone, located at the rear of the skull, connects with the cervical spine via the atlas, forming a stable joint that allows precise flexion and extension of the head. This joint is critical for maintaining natural posture and supporting athletic performance.

3. Joints: Precision in Mandibular Movement

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is one of the most significant joints in the horse’s head. It allows fine, coordinated movements required for cutting and grinding food, as well as controlling the bit during riding.

Dysfunction of the TMJ can present as:

- Head tossing or resistance to the bit

- Muscle asymmetry

- Reduced performance or discomfort during work

Studying the anatomy and biomechanics of the TMJ is indispensable for veterinarians specializing in equine dentistry, sports medicine, or physiotherapy, as it directly impacts the horse’s health, comfort, and performance

4. Facial Muscles

Facial musculature enables a wide range of movements for communication, prehension, and mastication. The masseter and temporalis muscles are the primary agents of jaw movement, while the orbicularis oculi, levator nasolabialis, and buccinator muscles contribute to facial expression and sensory feedback. These muscles are richly innervated by branches of the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII), making them highly sensitive indicators of discomfort or pathology.

5. Head Cavities

The head houses several interconnected cavities, each with a specific physiological role:

- Nasal cavity: Filters, warms, and humidifies inhaled air; also contains the olfactory epithelium.

- Oral cavity: Involved in prehension, mastication, and salivation; houses the tongue, teeth, and palate.

- Pharyngeal cavity: Serves as a shared passageway for air and food, connecting the nasal and oral cavities to the larynx and esophagus.

- Laryngeal cavity: Protects the lower airway and produces vocalization.

Understanding these cavities is key in diagnosing respiratory, dental, and swallowing disorders, all of which can affect athletic performance and welfare.

6. Main Vessels and Nerves

The equine head contains a dense network of arteries, veins, and nerves that maintain vital functions:

- The facial artery and maxillary artery provide oxygenated blood to facial and cranial structures.

- The linguofacial vein and maxillary vein ensure efficient venous drainage.

- The trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) supplies sensory input to the face and oral cavity, while the facial nerve (VII) governs motor control of facial muscles.

Lesions, compression, or inflammation in these pathways can cause sensory deficits, facial paralysis, or performance-related behavioral changes.

7. Functional Connections

The head is not an isolated system, it is dynamically connected to the neck, hyoid apparatus, and spine. The hyoid bones anchor the tongue and larynx, influencing balance and jaw mobility. Dysfunction in these connections can manifest as stiffness, headshaking, or poor bit acceptance. A whole-horse approach that considers anatomical interdependence is essential for accurate diagnosis and holistic treatment.

8. Clinical Importance

From a clinical and veterinary perspective, a detailed understanding of the sagittal section of the equine head—including the pharynx and larynx—is essential for evaluating, diagnosing, and treating a wide range of respiratory and digestive disorders. This three-dimensional anatomical knowledge allows veterinarians to accurately correlate clinical signs with the underlying structures, enhancing diagnostic precision and, ultimately, improving the horse’s quality of life.

Studies indicate that up to 40% of sport horses experience at some point in their lives a respiratory disorder of anatomical or functional origin that negatively affects performance. In many cases, these issues are exacerbated by insufficient knowledge of the functional anatomy of the upper respiratory tract, both in management and clinical assessment.

Among the most relevant pathologies are:

- Recurrent Laryngeal Paralysis: A Common and Limiting Disorder

Recurrent laryngeal paralysis (RLP), also known as roaring, is one of the most frequent upper respiratory conditions in sport horses.

It is estimated to affect 8–12% of racehorses and show jumpers, particularly large breeds such as Thoroughbreds and Warmbloods.

This condition arises from degeneration of the left recurrent laryngeal nerve, causing dysfunction of the arytenoid cartilage and partial obstruction of the airway during inspiration. Clinically, it produces a characteristic inspiratory noise and, in severe cases, can reduce respiratory capacity and athletic performance by up to 30%.

A precise anatomical diagnosis using endoscopy, combined with knowledge of the sagittal anatomy, allows for surgical interventions such as laryngoplasty or tie-back procedures, improving outcomes and reducing complication rates.

- Dorsal Displacement of the Soft Palate: Disrupted Airflow and Performance

Dorsal displacement of the soft palate (DDSP) is another frequent cause of inspiratory noise and reduced performance in young horses in training. Recent studies report an incidence of 10–20% in racehorses.

This condition occurs when the soft palate displaces dorsally over the epiglottis during intense exercise, partially obstructing airflow.

Detailed knowledge of the sagittal plane allows veterinarians to understand the relative positions of the soft palate, epiglottis, and pharynx, facilitating differential diagnosis from other laryngeal pathologies. Early identification and appropriate treatment—from training modifications to corrective surgery—can reduce DDSP episodes by over 50%, significantly improving oxygenation and athletic performance.

- Chronic Sinusitis and Dental Abscesses: Anatomy as a Diagnostic Key

Inflammatory processes of the paranasal sinuses, such as chronic sinusitis or dental abscesses, account for approximately 5–10% of equine clinical consultations.

The anatomical relationship between the roots of the upper molars and the maxillary sinuses—clearly visualized in the sagittal section—is crucial to understand how dental infections can extend into the sinuses, causing unilateral nasal discharge, foul odor, or facial pain.

Accurate anatomical diagnosis guides minimally invasive surgical procedures, such as endoscopic drainage or assisted dental extraction, reducing postoperative complications and shortening recovery times.

- Facial Trauma and Congenital Malformations: Anatomical and Surgical Challenges

Craniofacial trauma represents about 6% of injuries seen in equine emergency clinics, typically resulting from falls, collisions with obstacles, or transportation accidents.

Conversely, congenital malformations of the head and upper respiratory tract—such as nasal deviations, congenital cysts, or laryngeal anomalies—are less common, affecting roughly 1–2% of foals, but require detailed anatomical understanding for surgical correction.

The sagittal view of these structures facilitates preoperative planning, precise fracture localization, and functional and aesthetic reconstruction of the equine face.

In many cases, inadequate evaluation or lack of anatomical understanding can lead to serious complications, increasing postoperative mortality rates up to 15%, according to international clinical reports.

For veterinary students, mastering the anatomy of the horse’s head is not merely an academic exercise, it’s the foundation for clinical competence. Understanding the spatial relationships between bones, muscles, nerves, and vessels enables accurate examination, safe dental procedures, and effective pain management.

Modern veterinary education increasingly integrates plastinated equine specimens and 3D anatomical models, allowing students to explore these structures in a realistic and durable format. This approach bridges theoretical learning with clinical application, reinforcing both knowledge retention and diagnostic confidence.